Despite the UK’s relatively mild winters, poorly insulated homes mean a larger proportion of people in England are ending up in hospital due to cold-related illnesses than in Sweden.

According to Friends of the Earth (FoE), over the past five years hospital admissions for chronic lower respiratory diseases, such as bronchitis and emphysema, have been 40% higher per 100,000 of the population in England than in Sweden.

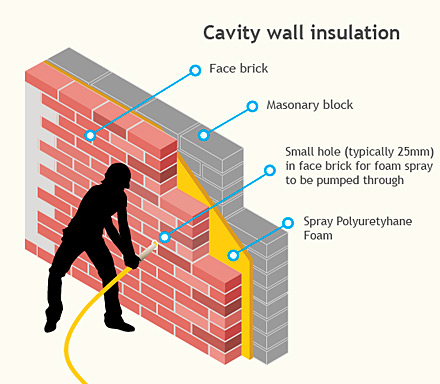

FoE says that the walls of houses in the UK typically lose three times as much heat at those in Sweden, due to a lack of cavity wall and loft insulation. Leaky and cold homes are often a cause of illnesses such as chronic lung disease, asthma, bronchitis and pneumonia.

Those conditions account for 3.2 million bed days in NHS hospitals at a rate of £275 per day, costing the health service an estimated £875 million, with the cost of GP and social care services pushing the bill up even higher.

Stays in hospital because of pneumonia have also been 27% higher over the past year, while 126% more people in England than Sweden have had to be admitted with asthma. According to Age UK, cold homes cost the NHS £1.36 billion every year.

Fuel poverty and “eat or heat” situations most adversely affect families with children. New research by national charity Turn2us shows that families with children now represent 45% of households in fuel poverty, while 81% of low income families in the private rented sector struggled with their energy bills in the last year.

The knock-on effect is severe, with 75% of families saying it is negatively impacting the health of their children and over half (53%) saying their children’s school work has suffered due to cold homes.

As part of its ‘Cut out the Cold’ campaign, Turn2Us also found that two-fifths (41%) of families have experienced illness due to their cold homes, while 56% are planning to reduce the temperature of their homes even further. The charity found that one in five families are considering taking out a payday loan to cover the costs they are unable to meet.

Cold homes have killed 46,700 people in the UK last five years, according to the research from the Association for the Conservation of Energy. The number of cold homes deaths across the UK in 2013 has been estimated at 7,400; nearly five times higher than deaths from road accidents (1,574), and more than carbon monoxide, fire and assault deaths combined, according to the Office for National Statistics.

So what is being done?

The new Fuel Poverty Strategy states that future governments will now be required by law to tackle fuel poverty by making the coldest homes in England more energy efficient. A new legally binding target requires a minimum standard of energy efficiency (Band C) for as many fuel poor homes as reasonably practicable by 2030. Regulations from April 2018 mean that private landlords cannot rent out properties with Energy Performance ratings below ‘E’.

The strategy also hopes to fund installations of central heating for properties that have none, and to extend the ECO and Green Deal schemes to build 500,000 properties that are easier to heat. In the coming months, up to £2 million will be released to support innovation pilots, not just in health but also for off gas grid, park homes and community energy approaches. £1 million more will be released immediately to grow local projects that help primary healthcare professionals such as GPs play a part in tackling fuel poverty by providing ‘warmth-on-prescription’ recommendations.

According to consultants Cambridge Econometrics, investing 3% of the UK’s infrastructure budget in energy efficiency would take two million homes out of fuel poverty by 2020, and add £13.9 billion annually to the UK economy by 2030, also passing on an £8.6 billion in energy savings per year by 2030, an average energy saving of £335 per household. Households in fuel poverty in the least energy efficient homes (Bands F and G) typically face energy costs that are £1,000 more than those in higher quality homes.

Additionally, making homes more efficient would cut carbon emissions from homes by 23.6 million tonnes per year by 2030, roughly equivalent to cutting the CO2 emissions of the UK’s entire transport fleet by one third.

Anh Tuan