Saturday, 28/02/2026 | 05:43 GMT+7

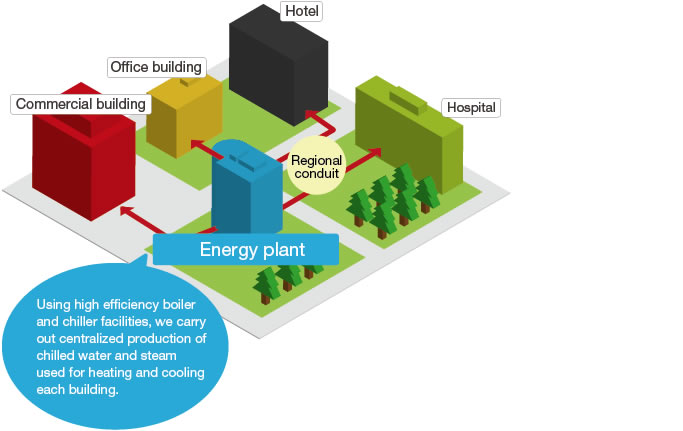

What is particularly clever about district heat networks is that they also capture and redistribute heat that would otherwise be wasted. The surplus heat produced by electricity generating stations, factories, server farms and public transport networks is funnelled into the network, eliminating waste, lowering carbon emissions, lowering fuel consumption and saving everybody money.

Fast forward 40 years from the original oil crisis and district heating networks provide heat to a whopping 63% of Danish households. Denmark has become a net exporter of oil and expects to remain so until at least 2018.

Here in the UK, a 2013 report by the engineers Buro Happold found that there is enough heat wasted in London alone to meet 70% of the city’s heating needs. If all the heat that is wasted were captured and put into district heating it would make a dramatic difference to our fuel bills, fuel poverty, carbon emissions and fuel security.

Having harnessed all the waste heat, the remaining requirement can be met by combined heat and power stations (CHPs). These are 20-60% more efficient than standard power plants because, as well as supplying electricity, they also provide heat. Standard power stations are only 30-50% efficient because the heat produced when creating electricity is wasted. In a CHP station the heat released during electricity generation is captured and used to heat homes and offices, making CHP power stations between 70-90% efficient.

Denmark has built an enormous network of pipes under its towns and cities, collecting waste heat from factories, incinerators, transport systems, and combining it with heat generated from solar thermal energy plants, wind turbines, and conventional gas and coal power stations, to produce a low cost and highly efficient heat supply.

Britain was far less affected by the oil crises of 1973 and 1979; we had recently discovered North Sea oil and gas. So while Denmark has spent the past 40 years developing a system that captures and harnesses waste heat and puts it into a grid with heat from CHP, Britain has spent the past four decades developing its gas grid. Now the North Sea reserves are dwindling and we are increasingly reliant of imported gas: in 2012 UK gas imports reached their highest since 1976 at 43%.

So the British government is trying to increase the number of households connected to district heating networks. The Department for Environment and Climate Change (Decc) would like to see the number of connected properties increased from a paltry 2% (just under 200,000 nationwide) to 20% by 2030 and40% by 2050. To facilitate this, Decc has made £7m available to councils to carry out feasibility studies for district heating systems.

More than 50 UK local authorities have taken the government up on its offer. Between them they have been awarded £4m and there is £3m remaining in the pot.

The Greater London Authority has set a target that 25% of its energy supply will come from decentralised sources by 2025. The first step towards this was creatinga map of London’s heat resources. The map shows where London’s power plants are, where its energy from waste plants is, its CHP sites and the proposed sites for heating networks.

The regeneration of the area around Kings Cross station in London will see 2,000 new homes built – all of which will be connected to district heating. Another 10,000 homes to be built on the site of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park will also benefit. Another scheme in Pimlico is already up and running, supplying heat to 3,000 homes.

Outside the capital, Sheffield, Leicester, Nottingham and Bristol are also investing in district heating. Bristol is developing the infrastructure in the local enterprise zone around Bristol Temple Meads railway station. Bristol’s assistant mayor, Gus Hoyt, sees it as “another way to entice people to Bristol, straight away we can say that their heating bills will be lower if they are connected to our district heating scheme”.

He says that, in return for the initial outlay on infrastructure spending, the city will see heating bills fall for local civic buildings, the hospital, the university and large swathes of social housing in the city centre. “One of our main drivers, other than the green agenda, is saving tenants money and reducing fuel poverty. Our council tenants will pay less and get renewably sourced energy at a competitive price,” he added.

Tim Rotheray, director of the combined heat and power association, says his organisation has never been busier: “Of late central government and local authorities have become really enthusiastic about this. They have begun to realise that this is something that has been working well across Europe for decades.”

Quang Minh

Consultation on the methodology for developing and updating energy consumption standards for four major industrial sectors

Consultation on the methodology for developing and updating energy consumption standards for four major industrial sectors

Opening of the 2025 Energy-Efficient Equipment and Green Transition Exhibition Fair

Opening of the 2025 Energy-Efficient Equipment and Green Transition Exhibition Fair

Energy-saving solutions and green transition promotion

Energy-saving solutions and green transition promotion

The 9th VEPG Steering Committee Meeting: Strengthening Coordination for Viet Nam’s Just Energy Transition

The 9th VEPG Steering Committee Meeting: Strengthening Coordination for Viet Nam’s Just Energy Transition